|

Back to Homepage

Part three : The tracing ofacross themillennia by DNA decoding

Every person is a leaf on the paternal and maternal DNA tree. Harvard University geneticist, Professor George Church was a co-founder of the Human Genome Project who once said:” Someday we'll have a complete pedigree of the entire human population. And everybody will be connected to everybody on a huge family tree, like Google maps.”

Once we discovered the secret in our blood expressed as nucleobase letters, we now have a clear and reliable clue to search for the Y chromosome Adam and mitochondrial Eve and thus the origin of our ancestors.

All these endeavors were originated from our genetic messages. Moreover, our genetic messages come from replications of DNA expressed as nucleobase letters passed down from generation to generation.

These replicated nucleobase letters retained authenticity, avoided aberrations but on occasion added genetic markers which can help to distinguish different ethnic groups. Markers on the Y chromosome and mitochondria become the milestones and signposts of tracing our genealogy.

At this juncture, let us tell 3 famous search stories: (a) the “search for Russia’s last princess” (happened in the early 20th century); (b) the 200 years old mysterious search “for Jefferson’s illegitimate child”; and (c ) the search for China’s Premier Cao Cao’s Y chromosome” (happened 1800 years ago). All these searches rely on these “milestones and signposts” abovementioned. And then when we will search for the “Y chromosome Aaron” (happened 3,300 years ago) it will not seem like a fairy tale from “The Arabian Night”.

I. Searching for Russia’s Last Princess

1. In the Name of Revolution

Tsar Nicholas II was the last ruler of Russia’s Romanov’s dynasty. In 1917, Nicholas II was forced to abdicate his throne during the turbulent Russian revolution. It was said that to thoroughly crushed the desire of the royalists to restore their former glories, Bolshevik leader Lenin gave the order to execute the tsar and his family. The executioner, Yekaterinburg, received this order on July 17, 1918 at 1 a.m. The imprisoned tsar, including his family and their four attendants were immediately wakened. The tsar family included Tsar Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra and their four daughters: 23 year old Olga, 21 year old Tatiana, 19 year old Maria and 17 year old Anastasia and 14 year old son Alexei. The four attendants were Dr. Eugene Botkin, male servant Alexei Trupp and female servant Anna Memidova and the cook Ivan Kharitonov. At first, they were told they to move to the basement downstairs for the sake of their safety. However, when they arrived in the basement, a car which normally carried corpses was waiting for them in the courtyard.

“When they got down to the cellar, they were still not alarmed to find several guards had joined them. Even when they were asked to line up in a group, they were not suspicious. Then the leader of execution squad approached the Tsar and took a piece of paper out of his pocket with one hand while his other rested on a revolver inside his jacket. Hastily he read the notice which condemned them to death. The Tsar was confused. He turned to his family, then to the guards, who drew their weapons. The girls started to scream. The firing began. First to be hit was Tsar; he slumped to the floor. The cellar echoed with the screams as they ricocheted around the room. It was pandemonium, and the room soon filled with smoke, making it even hard for the squad to pick out their target who were rushing to and fro in a blind panic. The order to cease firing was given and the victims were finished off with bayonets and rifle butts.”

These beautiful ladies, handsome young man, innocent attendants instantly became bloody corpse all in the name of revolution.

The above is an excerpt from the book entitled: “The Seven Daughters of Eve”. Seventy years after this mass murder, Brian Skyes, a molecular anthropologist, was asked by the new Russian government to confirm these people’s identities by using mitochondrial DNA from the corpses. He must be told a certain amount of truth. Therefore, the aforementioned events must be reliable.

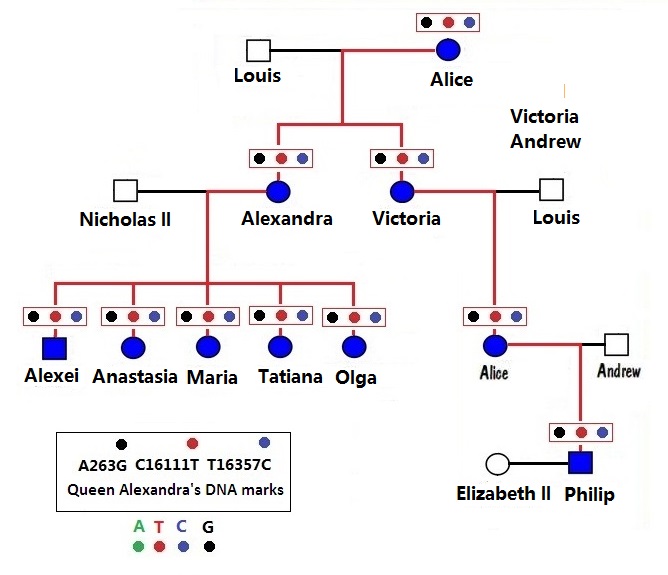

Figure 3-2 Empress Alexandra’s Maternal Mitochondrial DNA Genealogy Map

At the very top of the Figure one sees that Princess Alice had two daughters: Empress Alexandra and Princess (later Queen) Victoria. They each passed on their mother’s mitochondrial DNA with crystal clear manifestations of the colored-pearls on the mitochondrial necklace.

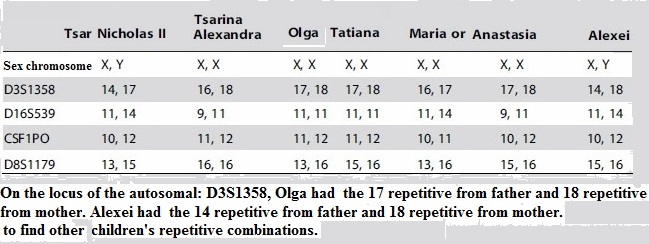

4. Confirmation of the Autosomal Chromosomes

The confirmation of autosomes is based on short tandem repeats (STR). It can be seen that on the five children’s D351358, etc.four DNA locus there were two STRs which were also found in their parents. For example in daughter Princess Olga’s D351358 STRs were 17 and 18 with STR 17 from her father and STR 18 from her mother. The other three autosomal loci also matched thus proofing that Princess Olga was the Tsar’s daughter.

Figure 3-3 Simplified results from the analyses of autosomal STR from the remains of the Tsar’s family

Just from the analyses of mitochondria and autosomes, scientists can then reveal the identity of the victims and debunk the 200 individuals who claimed to be Princess Anastasia.

Explanations: 1. Sex chromosome XY indicates male; XX for female; 2. Autosomal loci D3S1358, D16SS39, CSF1PO, D8S1179, the children must possess the same STR sequences as their parents. For example on the D3S1358 locus, Princes Olga had STR 17 from her father and STR 18 from her mother; Prince Alexie had STR14 from his father and STR 18 from his mother etc.

5. Confirmation from the Y Chromosome

The aforementioned report also showed a final conclusive evidence as the results of comparing the earlier blood sample from the Tsar when his was young. On April 29, 1891, during the Tsar’s visit to Japan Otsu city, one of the police men protecting him was assassinated. Fortunately, his life was spared but he suffered two cuts on his head. The shirt he wore on that day was preserved at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. From the DNA analysis of the blood stains on his shirt, the Tsar’s autosome and Y chromosome STRs were found to be exactly the same as those found in his skeleton. At the same time, researchers from San Francisco found the grandson of the cousin of the Tsar’s father, Andrew Andreevick, whose Y chromosome was similar to those found on the Tsar’s shirt and skeleton.

At this point, all the confirmatory task has been completed. We could put a period at the end of the story “search for the last Russian princess”.

|